Note: This is a guest posting from Zev Valancy, dramaturg for our Winter MainStage production of Anna Karenina.

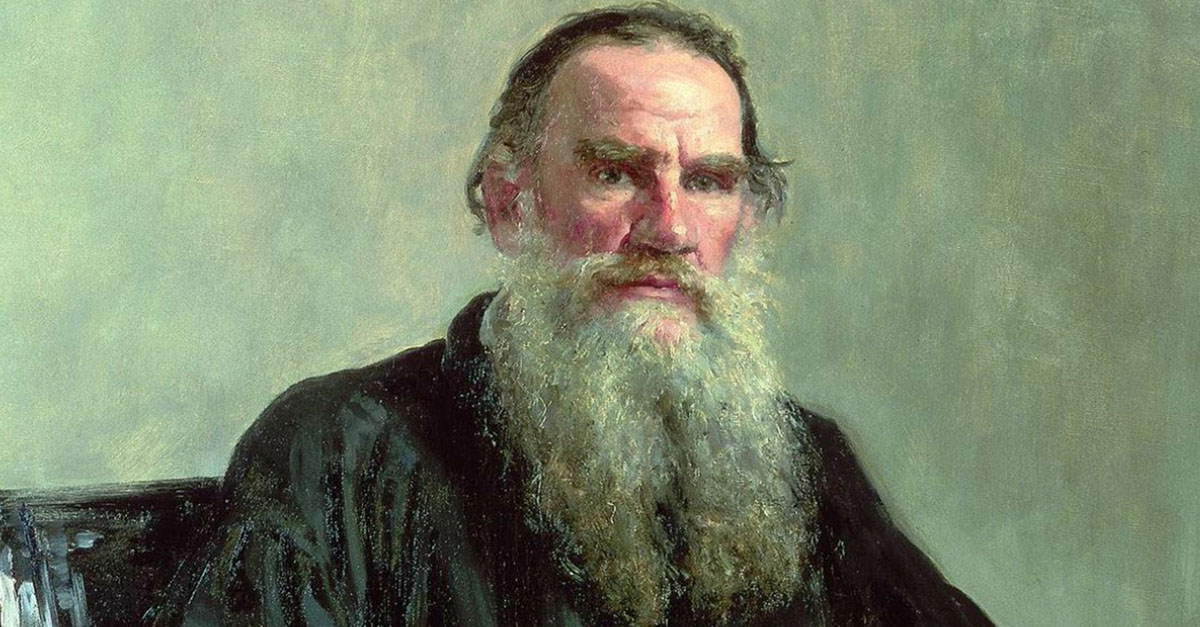

Count Leo Tolstoy (Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy in Russian—“Leo” was chosen for his English publications because “Lev” means “lion”) was born in 1828 on an estate 200 km south of Moscow. After failing to complete a college degree and running up major gambling debts, he joined the army and fought in the Crimean War, an experience which led him to start writing and influenced the increasingly pacifist, mystical version of Christianity which he practiced more fervently over the years. His ideals led him to found 13 schools for the children of the recently emancipated serfs (short-lived, due in part to police harassment), to work alongside the laborers on his estate, and to become an anarchist and an advocate for nonviolence (including a correspondence with a young Mohandas Gandhi).

Tolstoy wrote a wide variety of fiction and nonfiction throughout his career, much of which explored the ideals he espoused. He is best known, however, for his two major novels: War and Peace (partially serialized 1865-1867, published in its entirety in 1869), and Anna Karenina (serialized 1873-1877, published in book form 1878). Interestingly, Tolstoy did not consider War and Peace to be a true novel: It was set in the past, ranged widely in the characters on which it focused, included representations of real people, and had historical and philosophical essays interspersed into it. (Over the years, he referred to it by various terms, including “prose epic”.) Tolstoy called Anna Karenina his first true novel, due to its contemporary setting, engagement with contemporary politics and themes, and (relatively) narrower scale.

In addition to its explorations of themes related to human relationships and inner lives, the novel takes place against the backdrop of massive changes in Russian and European society.

Most important was Tsar Alexander II’s 1861 Emancipation of the Serfs, by which peasants who were formerly subject to significant controls by the wealthy nobles who owned their land—restrictions included the inability to own land, the nobles taking either significant fees or large portions of their labor, and restrictions on when and whom they could marry—gained a certain measure of freedom (though economic factors continued to hamper them). In addition to moral factors, the major reasons for this change included the perception that serf labor was economically ineffective, holding back Russian economic development, and a serious worry about a serf revolution. As Alexander II said: “It is better to abolish serfdom from above, than to wait for that time when it starts to abolish itself from below.”

The Emancipation of the Serfs was followed by a huge number of social and economic reforms, including reforms to the judicial system (particularly the introduction of jury trials), greater local government control (which the character of Levin is involved with before the novel starts, eventually leaving it in frustration), the introduction of the telegraph, massive expansion of railroads, and a freer press. The situation for women was also seeing significant changes, at least for the upper classes. While many elements of Russian society were extremely unfriendly to women, women had been able to inherit property since the 18th Century, and women in the upper classes were slowly gaining the right to an education (a question much debated in the novel).

This would bear fruit after the novel’s publication, with Russia having more female physicians, lawyers, and teachers than any other European country at the turn of the 20th Century. All of this tied in to “The Woman Question”, the catch all name for a philosophical, social, and literary movement focused on the rights and evolving position of women in the second half of the 19th Century. It was the subject of many essays and articles, along with many of the era’s most acclaimed literary works—Madam Bovary and A Doll’s House being two of the most prominent examples.

Anna Karenina has been widely acclaimed since its publication, lauded for Tolstoy’s grasp of character and language. It is seen as both the height of Realist fiction and a step in the development of Modernist fiction (particularly in the stream of consciousness sections before Anna’s suicide). It has seen a variety of English translations and been adapted to film, television, theatre, opera, and ballet.

Here at Lifeline, we are excited by the ways that this story from Russia in the the 1870s speaks to Chicago in 2018. In the next few weeks, we’ll be speaking to several of the artists who are helping to bring Anna Karenina to life–we hope you’ll join us!