From the Chicago Tribune

‘Middle Passage’ at Lifeline Theatre is both a swashbuckling adventure and a powerful indictment of slavery

February 28, 2020

By Chris Jones

★★★

When Charles R. Johnson wrote the novel “Middle Passage,” which won the National Book Award in 1990 for the Evanston-born writer, he immersed himself in the musings of nautical adventurers: Herman Melville, Jack London, Robert Louis Stevenson, even the mythology of Sinbad the Sailor.

But there is an important difference between those antecedents and Johnson’s story of the 1830 adventures of Rutherford Calhoun, a cocksure young citizen of Illinois who plays around on the seafront of New Orleans and then stows away on a ship, the Republic, mostly to avoid his debtors and a potential marriage to a schoolteacher about whom he is less than enthusiastic.

Callhoun is African-American, a freed slave. The Republic, he comes to discover, is a slave ship bound for West Africa. Its human quarry is to be the Allmuseri, a fearsome tribe in Johnson’s telling, known for their longevity, height, lack of fingerprints and, it is rumored, for the second brain that occupies the base of their spines.

Callhoun does not jump ship at the very idea but signs on anyway. He is to find out that the Allmuseri are not the only object of the voyage.

And thus Johnson tells a swashbuckling story rich with all kinds of themes, most of which explicate the inherent contradictions and complexities within American history and culture. The central figure is, of course, Rutherford, an initially invisible man who finds himself set adrift in a pool of chaos and must find his own moral center.

Lifeline Theatre is famous for its literary adventure shows that take its Rogers Park audience off on all manner of improbable voyages, the small stage filling with masts, actors being blown about in the wind, and the speakers crackling with the wind and the rain. As adapted for the stage by David Barr III and Ilesa Duncan, “Middle Passage” is not an original production; it was previously staged as “Rutherford’s Travels” by Duncan, now the artistic director of Lifeline, at the Pegasus Players in 2016. In her Tribune review, critic Kerry Reid called that first staging of the show “a ripping yarn, a thrilling bildungsroman and rich in comic detail.”

I’ll second all of that and add that it is unusual, now, to experience those qualities alongside this particular theme. But although “Middle Passage” is an indictment of the slave trade, racism and self-serving complicity by those who should have known better, Johnson (and Barr) still want to tell a swashbuckling and often funny story. If that sounds a mismatch of styles, the answer is that “Middle Passage” has many styles, depending on which moment you are watching, and that one of the key aims and achievements here, both by Johnson and Barr, is to focus not just on how the captured Africans were treated, but their elite stature, their majesty and their awe-inspiring intelligence. In Johnson’s imagination, the Allmuseri were close to immortal, and thus symbols of hope in the face of repression.

Certainly, there are physical limitations and also subtler pieces of theater in town, although Alan Donahue’s set certainly takes you out to sea and back again. There’s a deftly toned lead performance from the young actor Michael Morrow, evoking part a cipher and, maybe, an eventual man who finally knows himself. Add in a full-throated theatrical turn from Patrick Blashill as Captain Falcon, and Bryan Carter as one of big characters on the quay and you’re in the company of skilled storytellers in service of the explication of freedom. The show is great for anyone about 11 years old and up.

From Picture This Post

Adrift

February 25, 2020

By Spence Warren

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

“The social wheel is oiled by debt.”

In 1830s Louisiana, cunning rogue and recently freed slave, Rutherford Calhoun (Michael Morrow) is forced into a choice between marriage, indentured servitude to gangsters and stowing away aboard a ship bound for the high seas. His choice sends us on a decidedly different sort of swashbuckling adventure.

Lifeline Theatre Officiates A Marriage of Tradition and Innovation

Fog hangs in the air above a massive, detailed model of a sailing ship made of aged wood, metal and ropes which will serve as the multi-functional set while projections of an animated seascape illuminate the floor and back wall. The room temperature is low and – perhaps because the staff has anticipated the potential discomfort of guests – the back of each chair is draped with a blanket.

“Your judgement of character is worse than your cookin’!”

Morrow’s Calhoun, alternates between dialogue with other characters in the scene and direct address to the audience throughout the play. Every other actor in this crackerjack ensemble plays two or more roles. You too might find intriguing story insights contained within the choices of who plays who else in this tale of subjugation, lust, coming-of-age, betrayal, and redemption in the antebellum south.

A Tremendous Feat of Coordination at Every Level

Songs are sung a capella from behind the audience as well as behind and beneath the set, creating an organic kind of surround-sound. Many components of the set are functional; sails unfurl while characters tie off ropes and swing from the boom. Props and costumes are replete with minute detail. You too might find the fights and various other stunts to be visceral and acrobatic.

“Useful Boots”

It is the opinion of this particular reviewer that on the whole, despite a rather abrupt and melodramatic conclusion, MIDDLE PASSAGE is a masterfully executed, spellbinding piece of theatre that is HIGHLY RECOMMENDED for all audiences, particularly those who enjoy their high adventure with a social conscience.

From Chicago Theatre Review

Making History Come Alive

February 25, 2020

By Colin Douglas

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

Winning the 1990 National Book Award for Fiction, Charles R. Johnson’s novel is a sprawling two-and-a-half hour saga about a freed, young African-American man who comes to understand firsthand the horrors of the slave trade. Co-adapted for Lifeline Theatre by Ilesa Duncan and David Barr III, this ocean adventure is a tale of self-discovery and growth, detailing a young African-American’s journey toward maturity.

After leaving his native Illinois, cocky Rutherford Calhoun heads to New Orleans, where he intends to sow his wild oats in the decadence of the Big Easy. After arriving, he meets an enchanting, but prim and proper, young woman named Isadora Bailey. Calhoun charms the young lady, but Miss Bailey isn’t easily wooed by Rutherford’s sweet talk. She wants a commitment, so Isadora tries to blackmail Calhoun into marrying her if she’ll pay off his debts. To avoid the confinements of marriage, Rutherford stows aboard a sailing ship. What he doesn’t realize is that the Republic is a ship bound for the African coast on its mission to capture dozens of men, women and children who’ll be sold into slavery.

Rutherford befriends and becomes an assistant to the ship’s affable, heavy-drinking cook, Josiah Squibb. He also comes to like and respect the Republic’s moral First Mate, Peter Cringle. But, like the rest of the crew, Calhoun fears the ship’s tyrannical captain, Ebenezer Falcon, despite being taken into the brutal autocrat’s confidence and becoming his eyes and ears above deck. Johnson’s story takes the audience on a complicated, episodic and doomed voyage to the west coast of Africa, and beyond.

Along the way, Rutherford must overcome a number of challenges. Calhoun learns to balance an edgy relationship with the lunatic ship captain with a dissenting crew who continually threaten to mutiny. He figures out ways to crush all the fear and hatred thrust upon him by the Allmuseri captives, chained below deck. He attempts to survive a violent storm at sea that kills his most of his shipmates and destroys the Republic. Rutherford is rescued by another ship and, upon returning to New Orleans, he finds Isadora and his creditor, named Papa Zeringue. Ultimately, following months of danger, Calhoun has learned empathy, compassion for his fellow man and the importance of settling down to a wife and family. Ultimately, Rutherford Calhoun’s story ends happily.

This theatrical adaptation is one of Lifeline Theatre’s more involved, complicated dramas. Kudos to director Ilesa Duncan for keeping all of her ducks in a row and helping the audience to navigate this difficult, labyrinthine tale of the high seas. Johnson’s story is captivating and unique, especially with its African-American hero. The play presents a seldom-seen, sometimes misunderstood dark chapter of our history. The production is beautifully enhanced by a host of gifted, unseen talent. This includes a magnificent, awesomely impressive scenic design, by Alan Donahue; a palette of ever-changing, mood-enhancing lighting, contributed by Simean “Sim” Carpenter and Scott Tobin; sound and music designs by Barry Bennett and Shawn Wallace, respectively; and some incredible, moving projections, that bring the rolling waves and furious storm into this intimate venue, designed by Paul Deziel and Alex J. Gendal. Anna Wooden’s authentic period costumes put the icing on the cake. This is an incredible technical achievement for this literary-inspired theatre company.

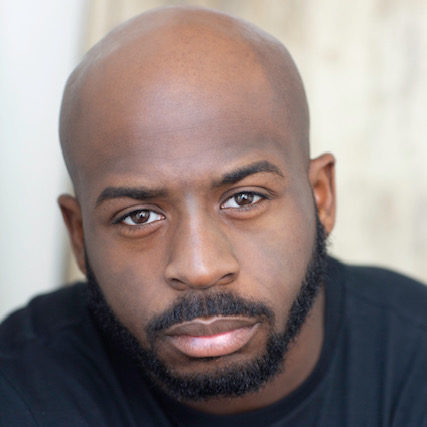

In addition, the eleven talented, highly versatile actors who bring this story to life are some of the hardest-working performers around. As Rutherford Calhoun, good-looking and charismatic actor Michael Morrow is terrific. Seldom if ever leaving the stage, Mr. Morrow is the heart and soul of this epic story. He easily takes the audience along with him on his journey to self-discovery and personal growth, and the audience comes to identify with Calhoun’s adventurous odyssey toward enlightenment.

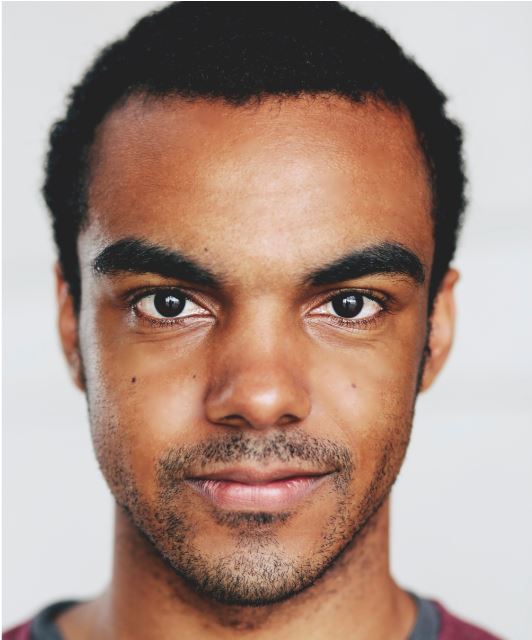

Morrow is ably aided by a cast of excellent supporting actors. Christopher Hainsworth is funny and touching as Josiah Squibb; the always impressive Andres Enriquez brings sobriety, class and stature to his portrayal of First Mate, Peter Cringle; Patrick Blashill is forceful and fearsome, as Captain Falcon. David Stobbe, as McGaffin, lends his combat skills to the action and a powerful singing voice to the melodic sea shanties that help create atmosphere; Shelby Lynn Bias makes a sweetly sophisticated Isadora Bailey; Jill Oliver displays her strength and versatility playing cabin boy, Tommy; Bryan Carter is a quiet source of ominous strenth, as Papa Zeringue; LaQuin Groves makes a threatening, towering giant of Santos; Hunter Bryant is intelligent and wonderfully commanding, as Jackson; and Demetra Dee makes and innocent and touching little Baleka. All of the actors double and triple as the townspeople, the ship’s crew and/or the African captives, making this cast all that more impressive.

This noteworthy, award-winning historical novel of the sea is a perfect offering for this company, especially during Black History Month. But this intricate tale of a young man’s journey toward maturity requires careful attention and listening by its audience. Lifeline Theatre’s brilliant cast and crew, under the tight direction of Ilesa Duncan, work hard to make history come alive, bringing this unbelievable adventure to the stage. For the smart theatergoer, however, the long voyage is definitely worthwhile.

From Windy City Times

March 1, 2020

By Jonathon Abarbanel

RECOMMENDED

Set in 1830, this classic picaresque tale concerns self-absorbed young Rutherford Calhoun, a Free Man of Color who is better educated than most men (black or white) of the era. Nonetheless, he chooses to be a petty thief and rake, especially when he travels to New Orleans to make his fortune. When his debts catch up with him, his only way out is unwanted marriage to wealthy Isadora (Shelby Lynn Bias). Instead, he stows away on a ship, the Republic, and is pressed into the crew, quickly learning it’s an illegal slaver bound for Africa.

Soon enough, Rutherford faces true perils through which he matures into a worthy human being. After picking up human cargo on the Guinea coast, and surviving a storm that cripples the Republic, Rutherford must thread his way between a crew mutiny, a slave rebellion and his promise to spy for ship Captain Falcon, who has befriended him for self-serving reasons. To reveal more would spoil things, except there’s something besides slaves below decks: there’s a mystical African god or creature that’s key to Rutherford’s spiritual awakening. Also, the ship’s ironic name is central to the tale, embodying Rutherford’s identity struggle long before we had a term for being both African and American.

It’s an engaging show, and why not? Lifeline Theatre has presented page-to-stage adaptations for nearly 40 years, so they have the narrative techniques and story-telling tricks down pat. Also, the cast features veteran Lifeline Ensemble members in key roles—Patrick Blashill as Falcon, Andres Enriquez as First Mate Cringle & Christopher Hainsworth as Squibb the cook—and they bring experience and versatility to the production.

As Rutherford Calhoun, Michael Morrow makes a very good impression in his Lifeline debut and really centers the show, which has been fluidly staged by Lifeline artistic director Ilesa Duncan. The production’s excellent design elements also add a great deal: scenic (Alan Donahue), costumes (Anna Wooden), lighting (Simean Carpenter, Scott Tobin) and projections (Paul Deziel, Alex. J. Gendal).

Middle Passage is adapted by Duncan and David Barr III from the award-winning 1990 novel by Charles Johnson. Their version was staged previously at Congo Square Theatre, notwithstanding which it still could use some refinements. First, Capt. Falcon is not depicted as villainous or cruel—especially compared to other 19th-century literary sea captains—so what inspires the crew mutiny? The real villain is Papa Zeringue, the black New Orleans criminal mastermind who partners in the illegal slave trade. He’s given almost comic treatment here, which doesn’t feel right. Also, Rutherford’s interaction with the mystical thing in the hold, which triggers his crucial spirit journey, could be longer and more intense. These refinements would make this worthy adventure even better.

From Buzznews.net

GREAT ACTING AND STAGING IN LIFELINE’S MIDDLE PASSAGE

February 28, 2020

By Bill Esler

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

Set in 1830, Lifeline Theatre’s Middle Passage, beautifully directed by Ilesa Duncan, is an exciting show: absolutely entertaining, well-produced and well-acted.

And yet, entertaining as it is, Middle Passage also recounts the horrific enslavement and transport of Africa’s Allmuseri people, their inhumane treatment by a cruel ship’s captain, and the desecration of their sacred possessions. How do these opposites co-exist in one play? Look to the source.

Based on the bestseller by Charles Johnson (adapted by David Barr III and the director), Middle Passage the book is a fictional first-person narrative by a 20-year-old freed slave, Rutherford Calhoun (Michael Morrow), who makes his way from Southern Illinois to New Orleans to sow his wild oats.

“She’s a town with almost religious pursuit of sin,” Calhoun says of New Orleans, in an aside to the audience.

Johnson gives us a picaresque novel, with a wandering young man, like other 19th century literary characters (think Thackeray’s Barry Lyndon). Both the book and the play recount from the first-person point of view, Calhoun’s experiences – good and bad passing before his eyes – during his adventures. So, as in life, the good and the bad, the lighthearted moments and the tragic, co-exist.

Like Barry Lyndon, Rutherford Calhoun is on the make in New Orleans, and without means – courting young ladies, but also running up debts. This comes to the notice of Papa Zeringue (Bryan Carter), a Creole mob boss holding all Calhoun’s promissory notes. Papa Zeringue tells Calhoun he must pay, or he will be thrown into the deeps of the Mississippi.

Thankfully for Calhoun, he has flirted (chastely) with Isadora (Shelby Lynn Bias), a young black schoolteacher from Boston, whose family has been free for generations. Isadora has some savings, and unbeknownst to Calhoun, negotiates to pay his debts to Papa Zeringue, on one condition – Calhoun will be forced to marry her.

When he learns of the plan, Calhoun stows aboard the ship Republic. When it puts out to sea, he discovers it is a slaver, on its way to Africa to pick up human cargo.

And with that, the story opens to an exciting, rollicking seafaring tale with all the trappings- storms, cannon fire, mutiny, betrayals, slave rebellions. Calhoun is there for selfish reasons – “Of all the things that drive men to sea, the most common disaster, I’ve come to learn, is women” – as one character puts it.

As an “everyman” character, we watch Calhoun avoid dirtying his hands in the fray, but eventually, he moves from aloof observer to responsible man, developing his moral compass through the trials.

The cast is uniformly good – really good – and most play multiple ensemble roles, as well as their principle character. Particularly notable performances were delivered by Patrick Blashill as Captain Falcon and Andres Enriquez as navigator Peter Cringle. Shelby Lynn Bias’s Isadora is both nicely written, and very well delivered – she is very 1830s Bostonian. Hunter Bryant (Calhoun’s brother Jackson), also, notably plays the role of a young slave learning English who bonds with Calhoun. Bryant launches convincingly into a somewhat lengthy delivery in an Allmuseri language.

Michael Morrow as Rutherford Calhoun carries the weight of the play on his shoulders, also making asides to the audience about the action or his feelings. Opening night, Morrow seemed a little uncertain in the beginning moments – but eventually warmed and really did command the role.

The set (Alan Donohue) is a lovingly crafted sailing vessel with multiple decks, stowage, working winche, mast and beam – all integrated to the projection design (Paul Deziel and Alex J. Gendal) and sound design (Barry Bennett). With this we feel for all the world we are at sea, particularly during storms and battles. A puppet parrot was less compelling.

The play originated at Pegasus Players in 2016 under the title, Rutherford’s Travels. But this version seems very strongly rooted in African storytelling culture, which taps a type of magical realism, to my mind (like Colson Whitehead’s Underground Railroad). Its title is far more resonant today: Middle Passage, the slave shipping route that represents the crucible of emotional and spiritual transformation from free, cultured Africans to impoverished American slaves.

From BroadwayWorld Chicago

February 27, 2020

By Emily McClanathan

RECOMMENDED

In Lifeline Theatre’s MIDDLE PASSAGE, the intimate Rogers Park venue transforms into the scene of a 19th century maritime epic. Artistic Director Ilesa Duncan and David Barr III adapt Charles Johnson’s award-winning 1990 novel for the stage, and Duncan directs. The sprawling tale follows a recently freed slave as he journeys from the gambling dens of New Orleans to the heart of the African slave trade and back again.

Michael Morrow stars as Rutherford Calhoun, a likable young rogue. Gaining his freedom upon his master’s death, he moves to New Orleans in 1830. With barely any money to begin with, Rutherford supports himself through petty theft and soon runs up gambling debts. After a flirtatious friendship with Isadora (Shelby Lynn Bias), a prim and proper teacher from Boston, Rutherford finds himself facing a forced marriage at the hands of his ruthless creditors. He escapes by stowing away on a vessel that turns out to be a slave ship, en route to pick up a “cargo” of captives from the Allmuseri tribe, a mysterious, fictional people from West Africa.

Rutherford encounters a vibrant cast of characters on his travels. These include cruel Captain Ebenezer Falcon (Patrick Blashill), kindly first mate Peter Cringle (Andrés Enriquez), the Allmuseri captives, and an ominous creature caged in the ship’s hold. With a crew mutiny and a slave revolt brewing, both sides try to enlist Rutherford’s aid. Meanwhile, Captain Falcon wants his services as a spy. This tense situation forms a dramatic backdrop for Rutherford’s coming-of-age story on the high seas.

With slavery as a central theme, the production doesn’t shy away from portraying its physical violence and psychological torment. The Allmuseri enter in chains, are inspected like animals on the auction block, and forced into infamously cramped quarters aboard ship. Beyond these obvious cruelties, we also witness the cultural suppression inflicted by the slave traders. Having grown up a slave, Rutherford envies the Allmuseri’s rich culture and history. In comparison, he feels that he has no past at all. And yet, even before they reach America, he observes a sad change in the Africans. In the hands of their captors, “they weren’t fully Allmuseri anymore.”

Composer and music director Shawn Wallace, working with Duncan as lyricist, plays an important role in developing the different cultures in this story. In the early New Orleans scenes, we hear the influences of African American spirituals and Creole folk music as the cast sing mostly a cappella, beating out their rhythms on improvised percussion instruments. On board ship, the ship’s crew carry off hearty sea shanties with gusto, showing their roots in the British Isles. In one memorable scene, the sailors’ jaunty tunes are juxtaposed with the haunting chants of the Allmuseri. Later, music becomes yet another tool of oppression when the Allmuseri are forced to dance a jig, “for exercise,” to the tune of a penny whistle.

As usual, set designer and Lifeline ensemble member Alan Donahue finds creative ways to make the most of the theater’s small stage. With the help of Paul Deziel and Alex J. Gendal’s projections, a single slanted platform with a mast becomes a ship. When a storm hits, Simean “Sim” Carpenter and Scott Tobin’s lighting and Barry Bennett’s sound design complement Nicole Clark-Springer’s choreography as the actors lurch across the deck.

Undoubtedly, MIDDLE PASSAGE is an ambitious novel to put on stage. With such an eventful narrative, several characters’ backstories feel underdeveloped or rushed in this adaptation. Still, Rutherford’s journey from boy to man is an impressive feat of storytelling, in large part because of its creative use of traditional adventure tropes to examine weighty issues of racism and slavery.

From The Fourth Walsh

Epic Journey to Self Discovery

February 29, 2020

By Katy Walsh

RECOMMENDED

In 1830s New Orleans, a young black man is running from debt and an arranged marriage. He escapes by boat only to find out he is now a stowaway on a slave ship. Ilesa Duncan and David Barr III adapted Dr. Charles Johnson’s riveting tale of a man challenged with confronting his identity, integrity and community. Duncan and Barr create this epic journey to self discovery. Rutherford Calhoun (played by an impressive Michael Morrow) deals with a series of tribulations from internal and external forces. Rutherford must choose between the life he wants and the one he is living.

The show is part musical (Shawn Wallace Composer/Music Director), part adventure, part romance, part history lesson… it’s a lot of parts! And it’s longer than the publicized two hours. Duncan, co-adapter and director, could have tightened the journey and the experience with some editing. Still, her ensemble is terrific. The charismatic Morrow charms everyone, the proper Shelby Lynn Bias, the crusty Patrick Blashill, the earnest Andrés Enriquez, and basically the entire audience. Morrow tirelessly transforms from amicable scoundrel to empathetic bystander to worldly savant. His metamorphosis is the heart and soul of this voyage.

Morrow is joined by a boat-load of characters aiding the robust storytelling. Many of the ensemble play multiple characters with distinction. A noteworthy Jill Oliver morphs between two sailors, one adorably cute and the other super creepy. David Stobbe is imposing as a malicious sailor and then almost cherubic-like as a chorus singer. Both Bryan Carter and LaQuin Groves are threatening thugs on land and terrified slaves by sea. And bringing the humor, the formidable Christopher Hainsworth (Josiah Squibb) uses his signature comedy timing and deadpan delivery to continually zing the one liners.

The design team (Alan Donahue – scenic, Barry Bennett – sound, Simean Carpenter – lighting, Paul Deziel and Alex J. Gendal – projections, Anna Wooden – costumes, R&D Choreography – violence) transport the audience to the high seas. Donahue’s wooden vessel is center stage rigged with mast and sails. Deziel and Gendal’s projections of the lulling waves are visible port side. The creativity is especially notable during squalls. The ensemble, the projections and the boom are moving in orchestrated chaos. Special nod out to Bennett’s sound design that startled me every time a turbulent storm was brewing.

Set sail for MIDDLE PASSAGE! The timely quest takes us on a thought-provoking ride to understanding.

From Third Coast Review

National Book Award-Winner Middle Passage Adrift On Stage

March 1, 2020

By Karin McKie

★★

Lifeline Theatre presents Dr. Charles Johnson’s 1990 National Book Award winner Middle Passage, directed by Ilesa Duncan, who co-adapted with David Barr III. The result struggles from the page to the stage. Self-described rogue, “social parasite” and freeman Rutherford Calhoun (Michael Morrow) arrives in New Orleans from southern Illinois in 1829, where he enjoys making a living as a pickpocket and petty thief.

As the title suggests, the story is somewhat about the horrific transatlantic slave trade, but also about a man running out on his debts, and a woman. Calhoun flees from “marriage hungry” Boston-born schoolteacher Isadora Bailey (Shelby Lynn Bias) by stowing away on the Republic, captained by Falcon (Patrick Blashill), alongside a motley crew of pirate-y stereotypes and a puppet parrot. An on-the-nose departure declaration says, “No Christian law holds water once you put to sea.”

After they are under way, Calhoun realizes the “three-masted bark” is a slaver that will capture and transport five “sorcerer” members of the Allmuseri tribe (along with an additional cargo of magic realism). In his search to understand freedom, Calhoun switches alliances among the crew, the captain and the enslaved, each group vying to divide and conquer. Calhoun is not Black enough nor white enough to fully fit into any side. One of the songs that serves as scene transitions is the chanting of “choose, choose, choose.”

The strange bedfellows end up adrift between Africa and America, literally and metaphorically, stuck in a Sargasso Sea-like liminal space searching for home, as the un-seaworthy ship (of state?), literally and metaphorically, falls apart, fulfilling the foreshadowing “she will not be the same ship that left New Orleans.” The Calhoun character’s constant self-narration makes the play’s emotional flow as choppy as the sea swells, and his ever-shifting promises make him unsympathetic.

Lifeline and set designer Alan Donahue accomplish their usual admirable job of packing a dynamic set into a small space, the angled wooden ship planks surrounded by effective water projections and lights by Simean Carpenter. Yet the result doesn’t match the weight of the title or the brief scene of humans in chains. What should have been massive emotional stakes becomes a tempest in a teapot.

From The Reader

Middle Passage is part voyage of the damned, part picaresque

March 3, 2020

By Kerry Reid

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

Lighting out for the territory, as Huck Finn put it, may be central to the American dream of liberty, but it’s also a false narrative of freedom. We see that clearly in Ilesa Duncan and David Barr III’s Middle Passage, adapted from Charles Johnson’s 1990 National Book Award-winning novel, which hit the boards with Pegasus a few years ago under the title Rutherford’s Travels. It’s now back under the original moniker at Lifeline under Duncan’s direction.

Rutherford Calhoun (Michael Morrow), a freed slave from Illinois in 1829, follows his licentious bliss to New Orleans, where he meets a governess, Isadora (Shelby Lynn Bias) who wants to make an honest man out of him. Escaping both Isadora and his debts lands him on a ship, the symbolically named Republic, bound for Africa to pick up a cargo of human beings.

What transpires is a battle for Rutherford’s soul and identity. Is he one with the white crew, who plot to take control of the ship? Does race, if not tribal affiliation, require him to help the Allmuseri, the group of captured Africans planning their own revolt? Or should he play both sides against the middle and serve as spy to Patrick Blashill’s Captain Falcon?

A mix of the historic and the swashbuckling with a scosh of magical realism, this production captures what is most arresting about Johnson’s original story. Morrow is splendid as the callow Rutherford forced to grow up and (in one mystical segment) confront literal ghosts of his past. If he sometimes seems like a cipher in the mix of larger-than-life characters surrounding him, that too is a reflection of how a Black man must negotiate what to reveal and what to hide about himself for the sake of his life and liberty.

From the Northwest Herald

‘Middle Passage’ offers gripping ocean adventure at Lifeline Theatre

March 8, 2020

By Rick Copper

RECOMMENDED

“Middle Passage” is a play revolving around a young man, Rutherford Calhoun, living on the sly as a petty thief and conman in New Orleans in 1830. A recently freed slave, Calhoun’s overwhelming self-confidence puts him into severe debt, which gets him into just enough hot water that he’s forced into a marriage he feels he does not want.

To get out of his marriage, Calhoun runs away, stowing away on a ship. Unbeknownst to him, it’s a slave ship. Here we find the crux of “Middle Passage,” as our swaggering protagonist soon finds himself in a delicate, almost overwhelming triangle – appeasing the captain, appeasing the crew that hates the captain and helping the slaves with whom he feels kinship.

Calhoun’s role is a huge one. Actor Michael Morrow runs with it as we watch his character mature from a swaggering man-child to a confident adult.

The crew are more pirates than they are sailors. Running a slave ship, they know exactly what they’re doing and only care about themselves – for the most part. The role of Josiah Squibb, who befriends Rutherford, is a great one, as he is the only pirate who displays any empathy. Christopher Hainsworth plays a great Squibb.

Captain Falcon is a scallywag for certain. He doesn’t give a parrot’s caw about anyone but himself. Actor Patrick Blashill made sure he took that role and squeezed it dry until every audience member held no empathy for his situation.

The rest of the cast had worthy performances, but I want to take note of two who really shined: LaQuin Groves as Santos and Demetra Dee as Baleka.

The set is magnificent, doubling as both a New Orleans pier and a listing ship, complete with hold. The pier/ship is wide, and there is plenty of room upstage for a series of well-choreographed fight scenes. These scenes were a delight to behold, and it’s obvious the entire cast worked very hard to get these down. A round of applause goes to both scenic designer Alan Donahue and choreographer Nicole Clark Springer.

Adding to the whole aura of being on the sea and the intense nature of the story is great work on the lighting and sound. There were a few moments during the storm scenes where I caught myself gripping my chair. A standing ovation to Simean Carpenter and Barry Bennett for their efforts.

My only beef with the play is the mysterious godlike creature “captured” and put on board the ship in the hold next to the slaves. If the reason it was on the ship was to wreak havoc, that’s fine, but it should’ve been more pronounced in dialogue than in action. In my opinion, this is akin to the briefcase in “Pulp Fiction” – some things are better left a mystery to be solved within an audience member’s head.

As it is, “Middle Passage” has a very deep story with a lot of arcs. When you base a play on a novel – as this one is based on a book written by Dr. Charles Johnson – it’s often difficult to condense. However, if director/co-adaptor Ilesa Duncan took this entire part out, it would not be missed.

“Middle Passage” is playing at the Lifeline Theatre in Chicago’s Rogers Park neighborhood until April 5. Lifeline is an intimate theater tucked into Glenwood Avenue right by the CTA Red Line/Purple express. On occasion, you can hear the train clickety-clacking by, but it does not hamper the performance whatsoever. In parts of it, it’s kind of an addition.

Because of the performances, stage, sound, lighting and fight choreography, it’s certainly worth the drive. Street parking is tight, but the theater has a shuttle system to ease that problem. Get there early enough to take advantage of it.