, http://lifelinetheatre.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/PP-Virtual-Play-FAQ-Updated.pdf, _blank

From Windy City Times

September 16, 2020

By Mary Shen Barnidge

For starters, what we’ve got are two wealthy young bachelors, two broke young bachelors, five genteel-poor young misses and one rich old battle-axe—but this is 1813 England, when only male heirs could legally inherit property, making the sole means of acquiring wherewithal ( or “digging for gold” as we call it nowadays ) sufficient to secure a comfortable future was to marry it.

Further complicating the negotiations necessary to remove the obstacles to true love bringing about a satisfactory match ( a “happy ending” in modern parlance ) was the snobbery discouraging fraternization between those boasting long and/or exalted lineage and those claiming pedigrees of more recent vintage.

Jane Austen’s groundbreaking novel originated the literary genre today known as the Regency Romance—a label often dismissed by our democratic age as frivolous costume-comedy. Austen’s firsthand familiarity with the grim sacrifices engendered by a social and economic system punishing the privileged and underprivileged alike reveals a universe encompassing a multitude of choices faced by individuals of all classes in search of values, identity and lives of, if not precisely joy, then contentment at the very least.

These goals require numerous auxiliary agents—parents, of course, and meddling kin, nosy neighbors and a bevy of servants—all mandating a crowded dramatic landscape. Fortunately, Lifeline Theatre has forged its reputation on big-stories-in-small-spaces arrangements and not even the cinematic live-stream format dictated by current social distancing restrictions can impede the narrative flow of Christina Calvit’s compact, but still comprehensive, adaptation.

Director Dorothy Milne and film editor Harrison Ornelas have likewise learned from early-spring experiments in video-staged performance: to prevent confusion arising from double-cast characters viewed in headshot range, each window opens on identification of the person it depicts at that specific time—a narrative device allowing us to witness reactions to the news taking focus, as well as enabling a vox-pop chorus of busybodies to keep us up to date on the expository gossip. Duet scenes employ Lifeline ensemble’s several real-life cohabiting couples to permit us a view of ballroom dancers waltzing with their faces outside of the frame, or a husband waving casually at smartphone correspondents over his wife’s shoulder. ( Did I mention that the production decor is modern dress-casual? )

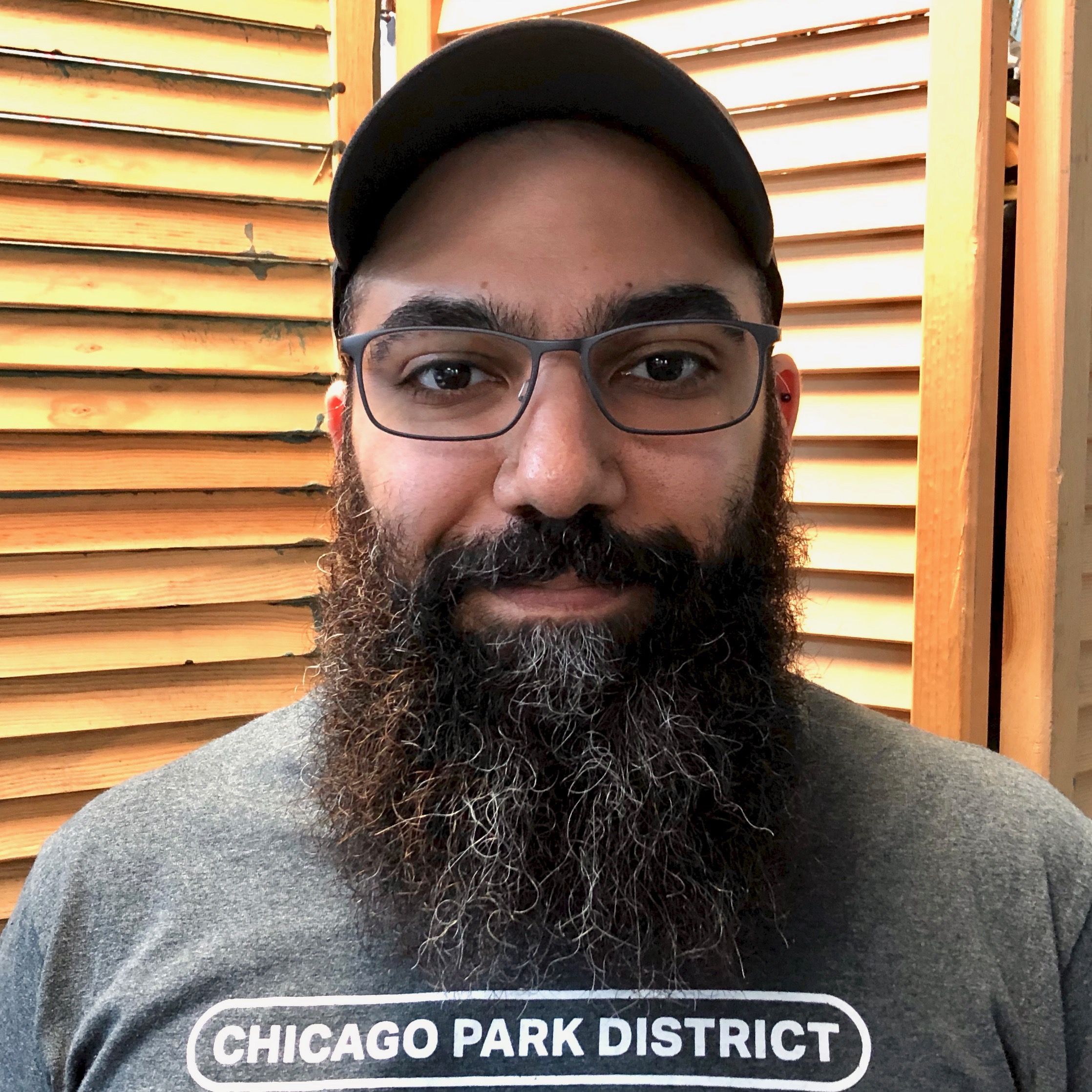

It’s not all techwizardry, however. The synchronicity achieved by actors after decades of experience swapping dialogue with one another, in a Rogers Park auditorium barely bigger than the “personal closets” ( “bedrooms” to us ) they now occupy, ensures a brisk pace and an intimacy enhanced by the close-up eye contact facilitated by the “asides” incorporated into Calvit’s text. When Samantha Newcomb’s irrepressible Lizzy asks us what we think of the latest contretemps, it’s all we can do not to reply—though if you’re watching from your sofa, feel free to roast the aloof Mister Darcy’s well-begun but ill-concluded marriage proposal, delivered by Andres Enriquez with affecting aplomb.

From The Reader

BoHo and Lifeline examine the public and private split

September 16, 2020

By Kerry Reid

The age of Zoom has created a split-screen metaphor for the changes in our private and public lives. We’re separated physically, but the world is invited into our personal spaces in a way that never happened in Cube Farmlandia. For theater pieces created at a distance and for online consumption, the dichotomy feels even more keen.

Increasingly, companies producing new work online are leaning into that dichotomy. That’s clear in two streaming shows that have premiered in recent weeks: BoHo Theatre’s The Pursuit of Happiness and Lifeline Theatre’s Pride and Prejudice.

In content and style, the pieces are completely different. BoHo’s show, subtitled A BoHo Exploration of Freedom, brings together 17 BIPOC artists under the direction of the company’s new executive director, Sana Selemon, in a virtual cabaret of song, spoken word, personal storytelling, and combinations thereof.

The show kicks off with Donterrio Johnson, the artistic director of PrideArts, singing and dancing in an empty theater to “I’ve Gotta Be Me,” a song from the 1968 musical Golden Rainbow, composed by Walter Marks and made famous by Sammy Davis Jr. At the end, we see a photo of vaudeville star Bert Williams, who was the first Black artist to have a leading role in a Broadway show. It’s an effective way to encapsulate the ways that Black artists have struggled to achieve success in a white-dominated cultural landscape without losing their own identity.

It concludes with Marguerite Mariama, a longtime artist and activist who notes that her political organizing began as a student protesting the “Willis Wagons”—portable classrooms that maintained de facto segregation in Chicago schools. Mariama’s recounting of her personal involvement in politics is set against a backdrop of imagery from the civil rights movement and graphic photos of lynchings. (BoHo has a content warning on the site for a reason.) Her rendition of “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” reminds us that the notion of “home” as a sanctuary has never been respected for Black people in this nation (the police killings of Breonna Taylor and Botham Jean made that all too clear), while her exhortation to “Stand Up” suggests that getting out of our homes and into the streets is a moral imperative.

Mariama chooses to perform against a solid black drop cloth, with her voice and the archival photos creating the emotional environment. But other performers allow us glimpses into the interior of their homes as well as their histories. (Tony Churchill deserves credit for his excellent editing work at blending all these segments.) Natara Easter performs a spoken-word piece that begins with “Well, I feel free,” and then takes us through all the ways she’s been made to feel ashamed about her appearance and expression—“the blackest sound in my laugh,” her smile, her way of speaking, her hair. (Easter notes that Black boys in her school were as likely to tease her about the latter as her white peers.) Throughout, we see Easter in her home; looking out a window to her backyard, writing in her journal, washing her face in her bathroom, and otherwise claiming herself in her space.

The theme of self-acceptance also comes through in Dillon Chitto’s piece about growing up gay and Native American in Santa Fe (“the gayest city in the southwest”) and the culture shock of attending a Jesuit seminary in Ohio. (The piece begins with a quick history lesson in how queer or “two-spirit” people, who were accepted in Native culture, were labeled as sinful when the colonizing Catholic missionaries arrived.) Chitto tells us that he has “a rosary in one hand, and a bagful of cornmeal in the other,” and creates his own personal trinity from “culture, religion, identity.”

Whether showing us the interiors of their homes or the inner workings of learning to blossom as a BIPOC artist, The Pursuit of Happiness is an exhilarating, intimate, and thoughtful 75-minute journey well worth taking. And I can’t wait to see all these performers again, live and in public.

Since 1986, Lifeline Theatre has thrice presented Christina Calvit’s adaptation of Jane Austen’s most beloved novel onstage. But the version available online now works beautifully at suggesting the tensions between private feelings and public behavior that undergird Austen’s world. Directed by Lifeline’s former artistic director Dorothy Milne, edited by Harrison Ornelas, and featuring a lineup of longtime ensemble members (including delightful real-life couple Katie McLean Hainsworth and Christopher Hainsworth as Mrs. and Mr. Bennet), the piece should resonate equally well with Austen purists (the dialogue remains faithful to the original) and those who are trying to figure out the rules of dating in a socially distanced time and place.

There are few attempts at costuming (save some plastic tiaras donned during various balls), and no attempts at creating a simulacrum of Austen’s world in the homes of the performers (though Caroline Andres’s period violin music adds resonant aural texture). But the story of Elizabeth Bennet (Samantha Newcomb) and Mr. Darcy (Andrés Enriquez) unfurls with all the wit and fire you could ask for. A moment when Newcomb’s Lizzy breaks away from the on-camera world to stride down the sidewalk (the only exterior shot in the piece), intent on visiting her sick sister Jane (Kristina Loy) not only shows us the forthright bull-by-the-horns candor underneath Lizzy’s careful exterior, but adds an extra layer of meaning in a time of pandemic and panic.

Taken together, BoHo and Lifeline’s productions reveal sophistication in style and material, and an admirable ability to take the limitations of our Zoom-saturated current reality and transform them into something fresh, personal, and wholly entertaining on their own terms.

From The Dueling Critics

September 16, 2020

Featuring Kerry Reid & Jonathan Abarbanel

LISTEN HERE